Mobile Enabled Digital Assistive Technologies (ATs)

Last week (28th to 30th September, 2020) we had the annual Forum for Internet Freedom Africa 2020, this year brought to you by The Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) in collaboration with Paradigm Initiative.

The #FIFAfrica20 had a wonderful array of sessions agenda’d at a variety of more than twenty-seven discussions across the three days with a great magnitude of experts in the ICT and associated fields. The sessions championed discussions on topics (inclusive but not limited to) Internet Freedom, Digital Rights, Digital Inclusion, Online Safety, Press Freedom, Artificial Intelligence, Strategic Litigation, Disinformation, Digital Practices, the Keep it on Campaign as well as ICT in the age of COVID19.

One of the great attributes to these whole sessions was the Digital-Inclusive-Agenda approach which cut across the needs and challenges of vulnerable marginalised groups to ICT access such as women and Persons living with Disabilities (PWDs).

Among my favourite sessions was that which was presented by GSMA, “We need to Support Growth of Digital Assistive Technology Innovation in Africa” with a very insightful presentation by one Clara B. Aranda-Jan with fellow panellists Nzomo Mbithuka (GSMA), Derick Omari (Tech Era) and Brian Mwenda (Hope Tech).

Assistive technologies (ATs) are assistive products and related systems and services developed to maintain or improve functioning and thereby promote well-being (WHO). ATs offers a means for enhancing functional performance when a person with a disability is unable to perform an activity that other people normally can complete (Edyburn, D. 2020).

This session gave an insight to PWDs Digital Inclusion and Exclusion in terms of accessibility, experiences, challenges, barriers and potential opportunities that we can bank on for the enhancement of Digital Assistive Technologies. There are already technologies and systems that have been designed and customized according to the needs and requirements with PWDs around the globe, but not all systems and governments can fully facilitate to fill the gaps and more so especially in developing countries such as Tanzania. Aside from a requirement of policies or/and guidelines to enable availability of ATs, it requires lots of funds, expertise and workable systems that favour an effective Digital Inclusion of the vulnerable group.

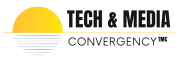

GSM has categorised three types of Digital Assistive Technologies as shown below.

The data above provides relevance of mobile phones and the emphasis of placing deliberate efforts of closing the mobile disability gap.

The GSMA research in the field “Mobile for Development, Assistive Technology ‘’ provides insight on Smartphones containing certain aspects of assistive technology that can help PWDs in the society. While other Assistive Technologies may not be easily accessible as a result of a variety of reasons such as affordability, the mobile phone on the other hand could be relatively accessible if more awareness is provided. As it stands, there is a disability gap that exists in mobile owners; PWDs are less likely to own a phone than non-disabled persons. At the same time, Women with Disabilities risk being digitally excluded compared to men living with Disabilities. Understanding how mobile phones could play a key role as ATs, could help address the Digital Exclusion for PWDs.

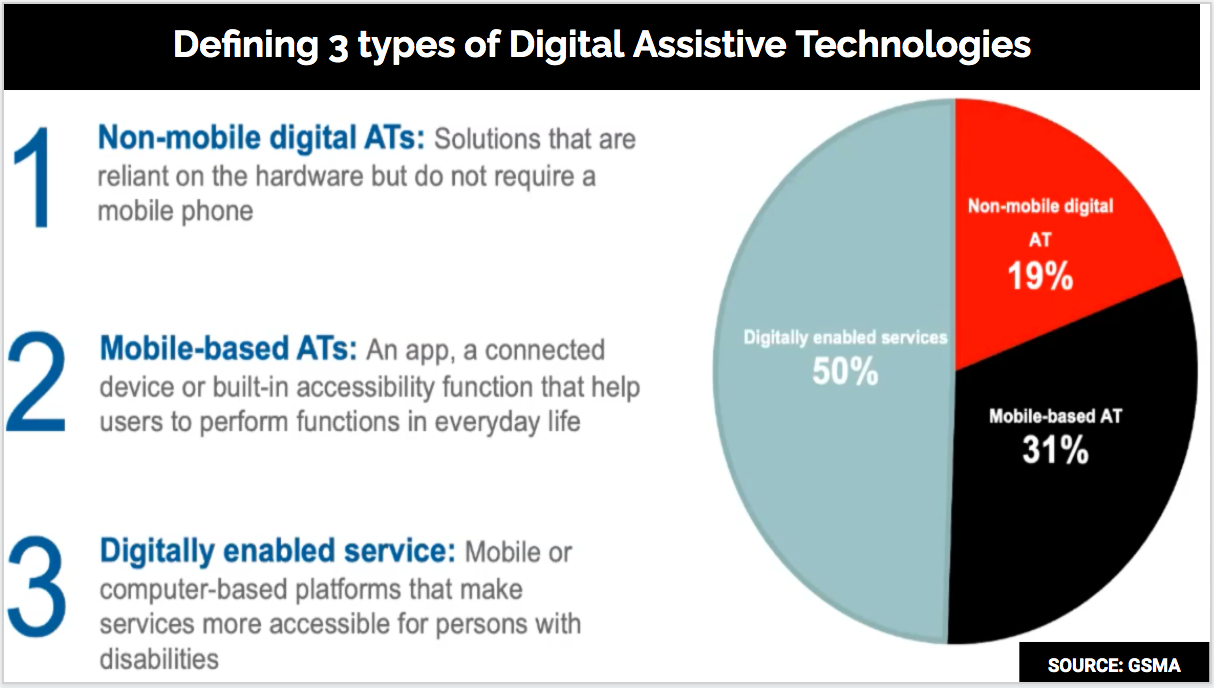

GMS also identifies five barriers to ownership and use of mobile as Access, Affordability, Relevance, knowledge and skills as well as Safety and Security; explained briefly below.

Addressing how mobile phones can be positioned as ATs in Tanzania has potential to be addressed effectively if this agenda could be carried by the corporate mobile companies such as Vodacom, TiGo, Airtel, Zantel, Halotel and Tanzania Telecommunications Corporation (TTCL).

Tanzania has the National Information and Communications Technology Policy (2016) and it specifies reservations for PWD in application of ICT by a supply of ICT gadgets to people with special needs. The policy acknowledges the importance of ICT to PWD’s in accessing details and information from the different sources of ICT tools in line with the legal framework regulating the ICT content pg.30 (3.10.1). Having policies and implementation has been polar entities in this aspect. Tanzania has several Digital Divide studies but has only focused on the term in general and not really considering PWDs.

According to national census data, the percentage of persons with disabilities in Tanzania is 8% of the total population (NDS). Still, there is a lack of comprehensive disaggregated data, including the specific challenges that persons with different types of disabilities face in accessing information and using ICT, also undermines the design and implementation of interventions that would improve their access.

To be able to understand the penetration of ATs, there is a need for research in the area. There is a lack of inclusive ICT data for PWDs while the very few available lacks enough information. Apart from the number of disabled in the country by type, sex and age group, there is a lack of conducted research for survey on Inclusive ICT for PWDs in formal learning Centres as well as informal learners scattered in different centres and associations managed by private institutions. Regardless having many policies and intervention such as the famously known MKUKUTA II; no real efforts are being placed directed to PWDs implementation, monitoring and reporting in terms of accessibility and use. MKUKUTA II (2010–2015) was the second National Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty (NPRSP), it acknowledged the weakness of the first PRSP (which had not considered PWDs) and mentioned PWDs and their interests with emphasis.

The above seems not to be a challenge for Tanzania alone, most of the developing countries are facing the same. In many low-income and middle-income countries, only 5%-15% of people who require assistive devices and technologies have access to them. Production is low and often of limited quality. There is a scarcity of personnel trained to manage the provision of such devices and technologies, especially at provincial and district levels (WHO). Late last year (2019)The Collaboration of International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) made a calling upon the governments and communication service providers in East Africa on the International Day of Persons with Disabilities (IDPD), to take decisive steps to enable meaningful usage of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) for persons with disabilities.

It should nevertheless be noted that this call of decisive steps are not only required from the governments but also the grass root levels. Institutions such as families, organisations, social-service based centres and all entities are required to be sensitive to barriers to address the needs that promote Digital Inclusion for everyone. The families are very well positioned to take the first step by understanding for instance that a PWDs needs the smartphone even more than the non-disable as well as banking on knowledge that there is an availability of assistive elements found in smartphones to promote Power Users. From the most accessible ATs, it has been shown that more than 50% are mobile boosted technologies.

The mobile device clearly stands out as an important tool for increasing means of assistive technologies to PWDs. By closing/reducing the mobile disability gap, we also increase accessibility to the group thus addressing the existing barriers to Digital Inclusion. One of the most interesting ideas that was explicitly shown was that In low and middle income countries, where access to IT is extremely limited, mobile phones have the potential to be bespoke and cost-effective tools for people with disabilities, clustering together multiple ATs in a single device.

There is a need for a call to action to mobile service providers to embrace technology so as to make mobile phones and services accessible to PWDs by considering features that could enhance access such as to the blind, low vision and hard of hearing. This could be launched as part of crucial movement towards Digital Exclusion of PWDs. With the rapid increase of mobile and penetration there is a need of review of services, practices, policies and programmes provided and implemented by stakeholders to embrace the practices that are inclusive of PWDs.

CEO | Asha D. Abinallah